With art-making, though, it's a collaborative endeavor, because we (our conscious selves) can partially drive the process. We may simply be vaguely thinking "serpent" or "dragon" while our hand moves around seemingly randomly, unconsciously. Is it moving randomly, and our eyes are seeing what we want to see?

Or is the hand responding to the semi-conscious direction? Who knows? Who cares?!

On top of that, even if the amorphous image is not in any way contrived in advance (maybe it's found in nature, or even made by another artist), we can consciously seek to specifically find what we want to draw, for example, a creature, a person, etc.

Some artists when coming up with, say, a creature concept, will simply "draw 'S' curves." Some scribble and scribble, with only a vague notion of what they are intending to produce, while constantly looking for anything that sparks their IMAGE-ination. That works! Me, I like to paint big soft blobs. Then I either let myself be hope to what comes, OR I decide in advance what I want to look for.

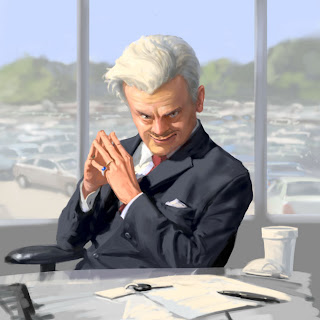

The first stage in this case was completely un-directed. Yet, like SOOO many people, for obvious reasons, I tend to see faces in everything. It doesn't take much. One thing that this process makes even more obvious is the PARAMOUNT ROLE OF VALUE IN SEEING AND PICTURE-MAKING. When your unconscious mind is struggling to make sense of what it sees, or thinks it is seeing something, you'll find this has very little to do with color. Yes, I am going to keep saying this in every post.

Anyway, now I seek to clarify what I see... or have decided to see... or think I see... just a bit...

The trick, though, is to keep the "cloud game" going. I want to clarify what I think I'm seeing, without killing it. Without turning into "that same old arm that I always draw" or whatever. The good thing with digital media is you can constantly look back at a prior version and go, "whoops, I lost it somewhere along the line." I do that a lot.

That right arm (on the left side of the picture) - what's it doing exactly? Is it coming toward us? Is it parallel with the picture plane? It's amazing how easily you can destroy the illusion of naturalness.

When you work this way you will produce shapes and forms that you might NEVER come up with consciously. You may see wonderful little hand gestures or facial expressions that open up whole new dimensions of picture-making for you. When working more consciously, we tend to produce the same kinds of faces, bodies, hands, poses, etc. I'm still not even sure to what extent "I" produced most of them. What it feels like is I SEE them, then very softly bring them out just enough so I'm sure others will see what I'm seeing.

Most artists when working this way (or similarly) tend to produce very similar imagery, over and over. Poses and faces may vary, but maybe it's always a figure floating in space, or a straight on face, or whatever. This seems contradictory - on the one hand you're producing new imagery that's very different from your usual habits... but on the other hand, you still may find that you very quickly start repeating your (new) self. The book Art and Fear postulates that maybe each artist has only a few stories to tell, maybe even only ONE story. So be it I guess.

Work like this has an organic and naturalistic quality that is very hard to achieve when consciously directing the work. But the fact that it can't be as easily consciously directed can limit its usefulness for certain kinds of commissioned work.

So, here's the "finished" piece. I call him "Warrior." He could be a lot more finished, I guess.